Study: Problem Gamblers’ Brains Process Losses More Slowly Than Recreational Gamblers

Caltech researchers find key differences in how recreational and problem gamblers learn from mistakes

2 min

When a recreational gambler loses money at the tables — or online, or betting on sports, or flipping a coin — they usually know, within reason, when to walk away. But problem gamblers often can’t, and researchers at Caltech have come one step closer to understanding why.

It’s because recreational gamblers and problem gamblers process losses differently.

In research published in The Journal of Neuroscience, researchers discovered that problem gamblers’ brains actually process losses more slowly than recreational gamblers, making it harder for them to learn from their mistakes.

“We think that people learn via a thing called prediction error: the difference between what you’re expecting to get and what you actually get,” John O’Doherty, the Fletcher Jones Professor of Decision Neuroscience and affiliated faculty member of the Tianqiao and Chrissy Chen Institute for Neuroscience, said in an interview published on the Caltech website. “If there’s a big discrepancy between the two, you’ll have a big prediction error, which means you need to update your learning so next time you will be able to make better, more accurate predictions.”

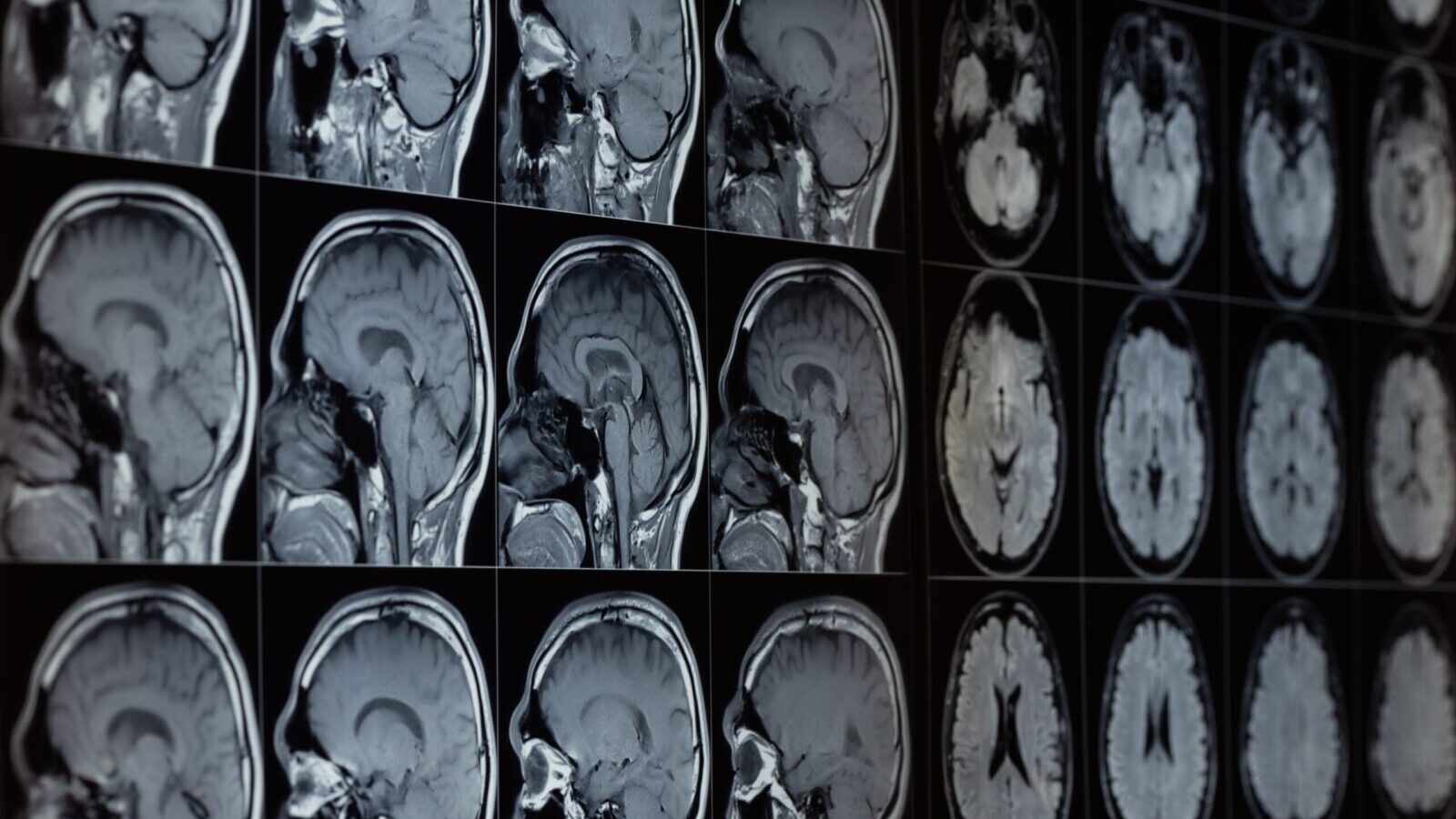

The research team, led by O’Doherty, studied 40 gamblers — 20 identified as “problem” gamblers and 20 as “recreational” gamblers. They carefully selected participants who had gambling experience but hadn’t received treatment for gambling disorders, in an effort to make sure the results wouldn’t be influenced by changed behaviors due to treatment.

Each participant completed gambling-related decision-making tasks while inside a functional magnetic resonance image (fMRI) scanner.

In one scenario, the participants were given the chance, over numerous trials, to develop strategies to help them increase the amount of money they could win. In a second scenario, the test subjects were told to learn from their losses and adjust their behavior to limit future losses. Participants who succeeded more quickly updated their prediction errors rapidly.

Both groups used the same brain regions in both scenarios, but problem gamblers processed the information differently, especially when dealing with losses.

Gambling with errors

“There are parts of the brain that learn in a slower way,” O’Doherty said, according to the article. “This means there is less updating after prediction errors and that learning happens gradually over time.”

This slower learning isn’t always bad, according to Kiyohito Iigaya, assistant professor of neurobiology at Columbia University and the study’s co-author.

“Slow learning is good when things are going slowly because it gives us accurate predictions of what’s going to happen,” Iigaya said. “But slow learning is bad when things change suddenly.”

As is the case when it comes to many forms of gambling.

The study found increased activity in problem gamblers’ anterior cingulate cortex and insular cortex — brain regions associated with slower information processing and prediction errors — during loss scenarios. This slower processing meant they were less likely to adjust their strategy when things weren’t going well.

And while the findings definitely showed a difference in the way the recreational gamblers and problem gamblers processed information, O’Doherty is not claiming this is a be-all, end-all situation when it comes to diagnosing and helping problem gamblers.

“The activation of these brain regions in problem gamblers is not going to be the whole story about what’s going on with problem gambling, because any disorder like this is likely to be very complex,” O’Doherty said. “There are probably also differences between individual problem gamblers. This is something that future research with a larger number of participants will need to unravel.”