The Truth About Why I Quit My Podcast

I didn’t know it at the time, but the turmoil was a blessing in disguise

6 min

Three swigs into the fourth IPA, 30 minutes before showtime, I was now sufficiently drunk enough to perform. Flip the switch, it was time to riff about legal sports betting on a new podcast, for a brand I had built with my own hands. In the scheme of things, the stakes were quite low. But due to all the pressure I had heaped on myself, my reality was about to implode.

While my Las Vegas-based partner Dave and I were set to record the next of only 10 total episodes of a podcast titled Get a Grip — ironic, because I was losing my grip on reality — at least two problems were colliding. Both of these problems existed entirely within me, owing to my faulty perception of things, fueled by an actual illness. At the time, circa March 2021, I did not know this.

The first problem: I had convinced myself that I needed to be inebriated to optimally convey my thoughts while serving as the industry analyst/expert half of our podcast duo. The second problem: I was, actually, struggling to speak and breathe, at least in a normal cadence, or really at all without being actively involved in an involuntary bodily process. I was under the spell of a strange form of obsessive-compulsive disorder known as Somatic (sensorimotor) OCD, where the compulsion centers on an involuntary bodily process. In my case, it was breathing, and the problem was my constant awareness of it. (Other iterations: Some people suffer from a fixation on the act of blinking, or swallowing, or even the constant awareness of one’s own nose.)

Recording at 10 p.m. eastern, hours after putting my 2-year-old son to bed, the right amount of alcohol did actually have the effect of somewhat curbing the OCD signals so I could focus on the task at hand — speaking, more relaxed and coherently, for an audience. It was the sweet spot that reminded me of playing beer pong in my heyday: uninhibited and functional, buzzing, feeling good. Now stay right there on the edge.

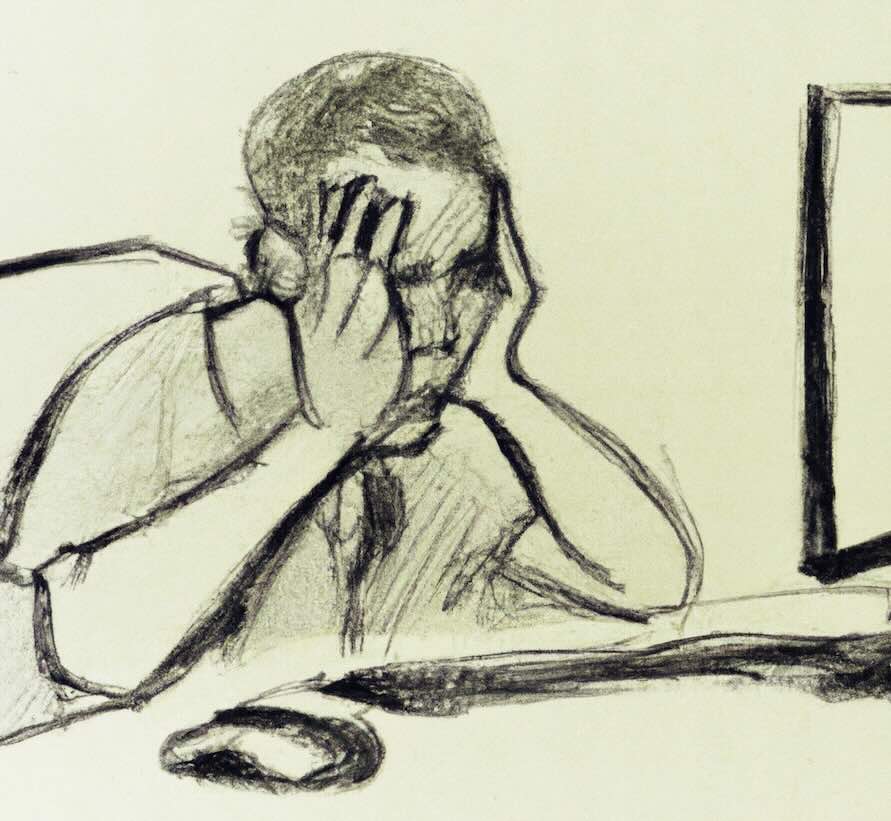

This was not sustainable. Or maybe it was, whether or not anyone knew I needed to numb myself in order to get out of my own way. But I couldn’t continue battling myself like this. It is and was immensely frustrating to lack the ability to think and speak clearly, while imprinting into a recorded track a version of myself that I knew did not represent the best of my abilities. This was going to break me.

After the one-hour recording, I cleaned up seven bottles of Victory IPA 8.0% ABV, shoved them in a kitchen garbage bag, and stowed the failure in a corner of the garage. I sat down on a plastic milk crate and dropped my head into my hands. Of course I knew something wasn’t right. But I still didn’t know what was happening.

That all began to change that weekend, when I found the start of some salvation in someone else’s podcast. About a mile into a jog on the treadmill, I flipped on Episode No. 263 of The OCD Stories podcast with Stuart Ralph and guest Dr. Steven Phillipson, and heard someone articulate, for the first time, exactly what had been plaguing me for about six years by this point.

A couple months later, after some difficult and half-honest conversations, I ended my own podcast. A few days after that, I began visiting Dr. Phillipson in New York City every Friday at 7 a.m. for 20 weeks straight.

What was happening

Obsessive-compulsive disorder manifests in some people when a part of the brain known as the amygdala is hyperactive. (Obligatory: I am not a doctor.) The amygdala helps regulate certain emotional responses including fear, anxiety, danger, and aggression. Basically, the warning and preparedness alarm.

Humans have survived some harrowing conditions and confrontations thanks in part to a brain that is always on alert. But there can be too much of a good thing, and I was experiencing it. Why my brain got caught in a loop that fixated on an involuntary process, breathing — that part I don’t know and probably never will. It may actually be rooted somewhere in perfectionism, as well as the resentment that results from being unable to achieve it. Letting go of this is an essential part of overcoming the very silly but totally debilitating disease.

Up to this point, I had attempted myriad home remedies to cure it. I had strapped a weightlifting belt around my midsection to regulate my airflow. I would work while lying on the ground so my diaphragm would be forced to automatically rise and fall on its own. I ordered all of the Orbit gum that Amazon.com had in stock, for when I was chewing a giant wad of gum, I could find a regular cadence in speaking and breathing. All of this nonsense and duct tape only ever served to lighten the symptoms a few degrees, for a short while.

If it is challenging to grasp how this actual problem is experienced, let me assure you, it is more perplexing to experience. Try timing your speech and your inhales/exhales at the very same time. The simplest and surest way to convey what it’s like is to compare it to having a song stuck in your head. It just won’t go away. The more you fight it, the stickier it becomes. Now sprinkle in frustration, anhedonia, and self-loathing, and you get the idea.

Even more mind-bending is to try to comprehend why it is occurring and why it must persist during every waking moment of one’s existence. The only escape, as anyone who has wrestled with depression knows, is sleep. But eventually, even sleep is hardly an escape from torment.

A lot of relationships suffered as a result of this silent battle. I declined most social invitations. Didn’t answer most calls. Lost contact with a variety of people from all walks of life. Skipped the gym if I was lacking my full aerobic capacity. I frequently found myself lightheaded due to the punctuated nature of my breathing. It’s difficult to be present in the moment when you’re lightheaded, and it’s challenging to not be overcome with resentment and rage when your own mind is sabotaging your ability to simply exist. I became irritable and short-tempered, and didn’t want to talk about the struggle. It was hard enough to exist, let alone explain to someone else something I didn’t fully understand.

When this thing started, it presented maybe about 10% of the time. By the time I arrived at weekly, intensive treatment, the OCD had snowballed into a dominant state, probably about 90% of my waking hours. I was a shell of myself.

Recovery

This time around, I began making another kind of audio track: I recorded all of my sessions with Dr. Phillipson. Then I played them back for myself the day after the visit. I took voluminous notes, and studied them before the next session. The man is a brilliant clinician and he had seen before what was ailing me and helped me understand it.

The way I got through it, eventually, was by realizing that the problem was not the overactive amygdala firing too-frequent panic signals. The problem was my response to it, constantly validating false alarms and responding to every siren. The brain’s job is to constantly produce thoughts, feelings, and ideas, but there’s also the gatekeeper, the person who decides what to do with all of this information. I needed to learn to just accept that my brain had a tendency to produce an avalanche of false alarms that caused me to fixate on my very act of inhaling and exhaling.

Ultimately I had to accept what might occur if I could not detach from this loop: I might not be able to access my full mental or physical capacities when engaging in conversation, or going for a jog, or reading a book to my son. But despite that, keep the plans. Live according to my values. Let go of the resentment. Just go with it and “live on the crumbs.” The resentment and anger was the glue keeping the whole system in place.

The recovery was not linear. More than 3½ years later, I still have good days and some not so good days, but I am pleased to report that for the most part, I have gotten out of my own way. Occasionally the OCD flares up, and I do my best, even if I’m a bit lightheaded or distracted.

Because I am a private person, it is not something I’ve ever wanted to discuss or disclose. Most of my closest friends will first learn of it through this very article.

I think at times I might have been ashamed that I was performing my jobs — work, father, husband, brother — at a level below my capabilities, due to the persistent impairment. But today, I don’t think I’m ashamed anymore. It’s the hand I was dealt, and I’m proud to have battled through it, and certainly fortunate to have had the resources and found the motivation to track down what proved to be the help I needed. The problem for me was never alcohol, to be sure. The booze was just a crutch to try to find some way to disarm the symptoms, so I could find the space to function. It also did not work very well.

It is cliche, but ultimately my goal in publishing this is to perhaps help someone else out there fighting a similar fight. It can be lonely, isolating, and absolutely perplexing. If any of this sounds familiar to you, take a look at NOCD or the OCD Stories podcast (here on Spotify), or send me an email or DM and I will at least try to point you in the right direction.

As for my podcasting career, well, I have no plans to return. But I have made periodic appearances with others, and I haven’t ruled anything out. In retrospect, it was a blessing that I chose to try something new, podcasting, which ultimately broke me and forced me to reckon with the underlying issue. I’m good now, but I’m not going to live in my comfort zone forever, wherever that takes me.