Paylines And Blurred Lines: In Sprawling Online Casino Ecosystem, Consumer Demand Is The Constant

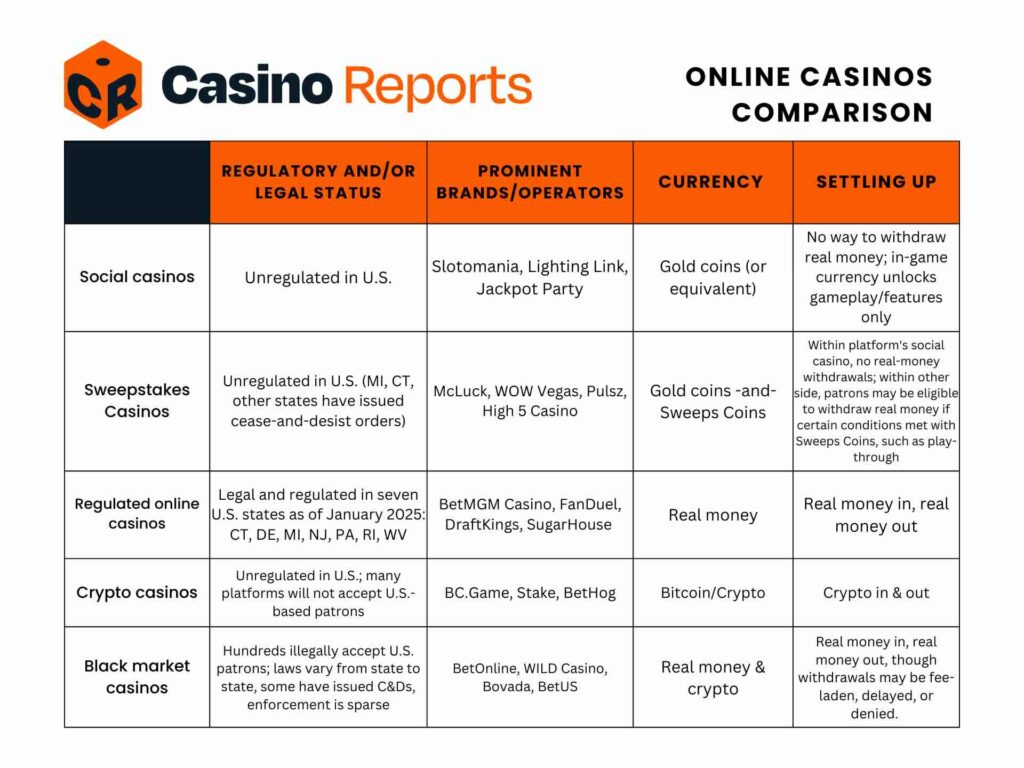

What distinguishes social casinos, sweepstakes casinos, real-money iCasinos, and others?

17 min

On Dec. 4, the almighty internet search gatekeeper, Google, unlocked the digital velvet rope and began to usher in a specific class of online casinos – social casinos – that it had previously barred entry, allowing them now to personalize ads for customers who may be interested in spinning a digital reel.

On the outside looking in, still confined within one of Google’s “sensitive interest categories,” remain real-money regulated casinos, social casinos using sweepstakes prizing (a.k.a. sweepstakes casinos), cryptocurrency casinos, and black-market casinos, among others.

In a rapidly evolving and expanding online casino ecosystem in which different operators are adhering to disparate rules and regulations across far-flung international footprints, the differences and similarities between the types of casinos has become critical.

Not just for Google, which positioned itself to collect significant advertising dollars from a casino category generating an estimated $7-10 billion annual revenue and growing; the lines of demarcation between social casinos and other types are being parsed out in various legal filings, model legislation drafts, gaming industry boardrooms, and within the investor class as well.

For example, a class of plaintiffs in a lawsuit filed in the Southern District of New York (SDNY) on Dec. 3 alleges that Virtual Gaming Worlds (VGW) — the largest of the sweepstakes casino operators — “misleadingly describe their websites as ‘social casinos’ to promote the deception that they are free to play and for entertainment purposes only.”

In pure social casinos, there is no way to redeem any cash prizes. The games revolve around one currency, typically gold coins, and those coins unlock play, experiences, and add-ons, but do not have any cash value. Not so at sweepstakes casinos, where the platforms are bifurcated into a free-to-play (or freemium) side resembling the social casinos, and a sweeps side where users may deploy “sweeps coins” in casino games. The platform may issue these sweeps coins via email promotions (or via regular mail), for example, or users may purchase packages of gold coins that include sweeps coins. Ultimately, because the platform doesn’t require a purchase or substantial time/effort to access the freemium casino, the element of “consideration” is eliminated, and therefore it meets the criteria as a sweepstake or contest, according to sweepstakes laws in most states.

In the SDNY lawsuit, the latest in a recent legal offensive against VGW, plaintiffs allege that the inclusion of redeemable prizes tied to gameplay changes this classification of “social casinos” to something else, calling it a “bait-and-switch.” The lawsuit alleges multiple violations of the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations (RICO) Act. Google and Apple and their respective Play Store and App Stores have been called into question, and into court, alongside VGW to answer for their roles in distributing the various apps. You can expect that the tech giants will vigorously defend themselves and perhaps get the cases dismissed on jurisdictional or procedural grounds.

In the interim, sweepstakes casinos press forward into the massive gray void created by the broad unavailability of regulated online casinos and by the widespread demand for digital casino platforms.

Reel similar

Having highlighted some differences between the types of online casinos, we turn to similarities between social casinos, sweepstakes or “social sweeps” casinos, and regulated, real-money online casinos. The list is fairly extensive.

For starters, on social casinos like the popular Slotomania from Playtika, users can still spend, and lose, as much money as they’re willing in the name of casino-style entertainment.

All three casino subtypes offer largely the same casino games. Lots and lots of slot machine games. Many have a selection of digital table games. Some but not all of them offer live-dealer games, powered by real human dealers in studios.

Several of Playtika’s social casino brands also recently began to feature some of the same exact IP-driven games currently only available on real-money gaming platforms. The company announced on Dec. 20 that it was hooking up with Las Vegas-headquartered International Game Technology PLC (IGT), a prominent slot machine and real-money gambling industry supplier.

“Starting this month and rolling into 2025, IGT slot titles will appear in Slotomania, Caesars Slots, and House of Fun,” read the release. “The first fan-favorite, Cleopatra II, will debut in Slotomania beginning December 26, 2024, with more top-performing IGT slots slated to follow throughout the next year.”

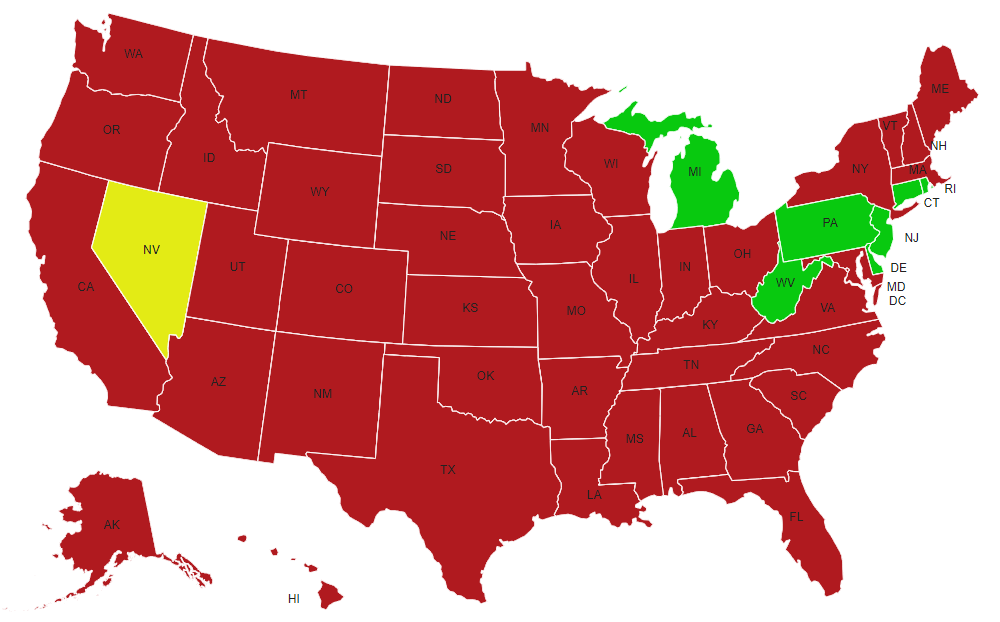

Presently in the U.S., Cleopatra II also appears on the regulated online casinos operated by the likes of FanDuel Casino and BetMGM Casino, where there are no pretenses about currency or coins. But for now, the regulated casinos are legal in only seven states: Connecticut, Delaware, Michigan, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, and West Virginia. (In Nevada, online poker is legal, but online casino games vs. the house are not.)

That leaves the vast majority of demand for online casinos in the U.S. currently to be satisfied through various other channels.

The strongest and most unambiguous common thread across the various iterations of casinos — including the crypto casinos and black market outfits — is that there is enormous demand for these casino games.

Allan Stone is the president and co-founder at Acquire.bet, a company that helps gambling industry clients understand consumer behavior and helps operators convert potential players and keep them engaged on their platforms. Stone spoke with Casino Reports about the online casino ecosystem.

“At our core, we are consumer behavioral scientists, and one thing I can tell you that’s universal: People want these products,” Stone said. “In our view of the world, where gambling is competitive entertainment — and call it what you want to call it, there’s real money, there’s social, and there’s sweeps — those are all forms of competitive entertainment. At the end of the day, people are putting money down in order to be entertained. That’s all it is. Consumers are saying what they want, they’re showing what they want with their wallets, so why not give it to them?”

It’s a fair question, while the status quo currently has swaths of American consumers stepping into an unregulated digital void to get what they want. And any change to that will require the difficult task of negotiating a multitude of stakeholders and the conflicting interests in politics, economics, and, of course, societal well-being.

They’re social and they’re profitable

Prior to Google’s advertising policy shift, the search engine and advertising behemoth grouped social casinos, alongside all other casinos, in the gambling designation as a “sensitive interest” category where legal restrictions, namely a person’s age, applied.

“The Gambling in personalized ads sensitive interest category will be updated to explicitly exclude social casino game app campaigns,” the company wrote in a November post announcing the impending change. “[Google] will begin to allow these ads on December 4, 2024. All advertisers will gain the ability to personalize online social casino game App ads by the end of March 2025.”

While it is as-yet unclear exactly which companies have or will flip the advertising switch, and to what extent they’re advertising, the ads likely will come from at least some of the following groups. According to Eilers and Krejcik Gaming, the eight biggest and most profitable social casino game makers are as follows:

- Playtika

- Pixel United (Aristocrat Gaming)

- SciPlay (Light & Wonder)

- Netmarble

- DoubleU Games

- Take-Two (parent of Zynga)

- AppLovin

- PlayStudios

Eilers and Krejcik Managing Director of Digital & Interactive Gaming Matt Kaufman helped shed light on what drives roughly $10 billion of revenue generation for the social casino industry.

“The overwhelming driver of monetization for all social casino companies, whether using a traditional model or leveraging a sweepstakes model, is sale of in-game currency,” Kaufman said. “People purchase coins, and the coins extend your ability to play the games.”

“Sale of currency allows people to have premium experiences or to extend their gameplay,” Kaufman expanded. “Having more currency can also sometimes have benefits with respect to meta features like clubs and leaderboards, where users compete with other players. Some social casino platforms also sell access to in-game features or purely aesthetic items like avatars, but those typically represent a very small portion of revenue compared to sale of coins.”

In Kaufman’s view, the similarities between social and sweeps casinos are far greater than the differences, because regardless of the specific monetization and promotional model being used, the underlying products are still social casinos.

This is echoed by PlayStudios CEO Andrew Pascal, who noted during the company’s Nov. 4 third-quarter earnings call that it was eyeing sweepstakes as a promotional mechanic.

“We believe that the emergence of sweepstakes as a promotional mechanic and a driver of monetization is proving to be significant. The scale and magnitude of the games and services that are exploiting sweepstakes is very substantial today. I believe it’s a $3 billion plus market. And if you look at the games and the underlying services that are being provided the content, they’re free-to-play social casino products.”

Yet, for some stakeholders, the view is that there exists a clear and unmistakable distinction between social casinos and sweepstakes casinos.

“It’s not complicated,” Light and Wonder Head of Government Affairs Howard Glaser told Casino Reports. “In sweeps, you pay real money for a chance to win cash money. In social you don’t. That’s it.”

That takes us back to the mechanics of the games themselves — and the chance to win money — and the ultimate irony that many if not most players may not even care whether or not they can win money.

“Whether users can actually win money back, that’s just the mechanic,” said Stone. “What we have found about user behavior is that the ability to win money does not create or deter any type of additional incentive for the user. It’s almost as if users know that they’re simply playing to be entertained. If they can win money, great, but at the end of the day, as long as they’re getting commensurate value for the money they’re putting down for entertainment, they’re OK with it.”

In other words, user behavior indicates that players just want to play the games, to be distracted, or entertained, compete against others, advance through levels, perhaps some combination.

The thornier matter is whether policymakers and stakeholders let people access the online casino products they want, and to what extent.

Soccer moms and male whales

In terms of actual gameplay, the inventory across the different channels — social casinos, sweeps casinos, real-money casinos — is fairly similar. Consider the Cleopatra crossover example.

That is an oversimplification but the point is that most casinos will have a wide variety of slot titles, some card and dice games, maybe some live dealer, with a smattering of exclusive titles integrating some third-party intellectual property.

The vast majority of casino play centers on slot games. Now close your eyes and picture the average person who has downloaded and actively plays Slot-o-Mania (Playtika), Lighting Link Casino (Pixel United), or Jackpot Party Casino (Light & Wonder). If you have in mind a female 35-and-up, perhaps your quintessential “soccer mom,” that’s the most common profile, per industry sources.

Which isn’t to say that plenty of men don’t dabble — they do — and in fact the “whales” or the biggest spenders are typically men, while female players, on average, are the better players who typically drive higher lifetime values (LTV) to the operator, according to Stone.

But zooming back out for a moment, contemplating the whole universe of casinos, Stone observed that the online casino consumer appears to be attracted to the gameplay, the action, in almost the same way, irrespective of the structure and kind of casino.

“It almost doesn’t matter to the players what the mechanic is: whether it’s social, sweepstakes, or real money,” Stone said. “At the end of the day, it’s the same to them, right? Other than the fact that with sweeps and with social casinos, they might be artificially limited in terms of what they can do or access, because of how those products are priced. Otherwise, player behavior doesn’t skew in terms of average session duration. The time-spent comparables across those three verticals are virtually indistinguishable.”

Stone also highlighted at least one advantage for social and sweepstakes casinos, versus real-money gaming casinos: the power of scarcity.

For example, on social or sweeps casino platforms, some of the content is locked, or access must be gained by hitting certain thresholds of spins or coins earned, for example.

On real-money casinos, where users are posting up real money, they will expect to access the casino’s full-suite of games without having to pay some additional entry fee, which in some cases may just be time.

“They can artificially create some scarcity that incentivizes a deeper connection to the game,” Stone said of the social/sweeps products.

Another strength that the social and sweeps casinos have realized, according to Stone, is that they “highlight the hooks” more than real-money casinos.

“What I mean by that is, let’s say you’re playing a progressive jackpot slot right in the sweepstakes casino. In the real money world, maybe they’ll display a little meter on the side that you need to fill up and when it does, it’ll trigger a bonus. In the real money world, that meter is just there. Whereas in the social and sweepstakes casino world, they’ll actually draw your attention to it, that you’ve almost reached it, and build some excitement. They’ve just done a better job of calling attention to some of the hooks that make those products a bit more engaging, sticky, and interesting.”

Consequences of disruption

Of course, there are disadvantages to operating a sweepstakes casino in today’s environment. There is opportunity but also challenge in navigating a product in an unregulated environment, which is inherently uncertain.

Get too big or successful or creative in an arena, or threaten someone else’s pot of gold, and you eventually become a target. This is the lived experience of VGW.

VGW, if only a proxy for now for the full lot of sweepstakes casino operators, much in the same way that Bovada is for offshore black market sportsbooks, is now a target in multiple theaters: It has drawn the ire of California tribes; it has angered competitors favoring or engaging exclusively in regulated spheres; and of course it has become a recent magnet for class-action lawsuits from consumers, and some opportunistic lawyers, who claim to have been duped or defrauded by sweepstakes casinos.

One attorney who has represented sweepstakes casinos, Bill Gantz, a Duane Morris partner and lead of the firm’s gaming industry group, has been quick to point out that social casinos have been defending, and settling, civil lawsuits based on gambling loss since 2015.

“This is not just about sweepstakes — this is also about freemium [products] too,” Gantz said during an appearance on SBC’s iGaming Daily podcast on Dec. 11 with host/reporter Jessica Welman.

“All of those things said about sweepstakes are true about freemium [products]: It’s unlicensed, it’s unregulated, it’s been accused of irresponsible gaming, it’s been accused of underage access. People spend hundreds of thousands of dollars on these sites and they only win gold coins. All of those allegations are in the lawsuits, and they’ve been raised as to freemium products only, if you really want to know what’s been happening in the litigation.”

According to an analysis by Macquarie last month, as reported by Compliance & More on Dec. 11, the team dismissed the notion that sweepstakes casinos might be cannibalizing from regulated iCasinos. Rather, they wrote that it is “likely sweepstakes was cannibalizing social casino, suggesting the latter format contains a significant cohort that plays because of the lack of legal iCasino options.”

This is based in part on trends dating back to the pandemic peak and an inability, so far, to replenish user bases, in part due to the probability that sweepstakes platforms are “likely peeling away users.”

These trends may soon change, thanks to Google’s policy shift on personalized ads for social casinos — and not any of its casino peers — and the advertising budgets that will follow.

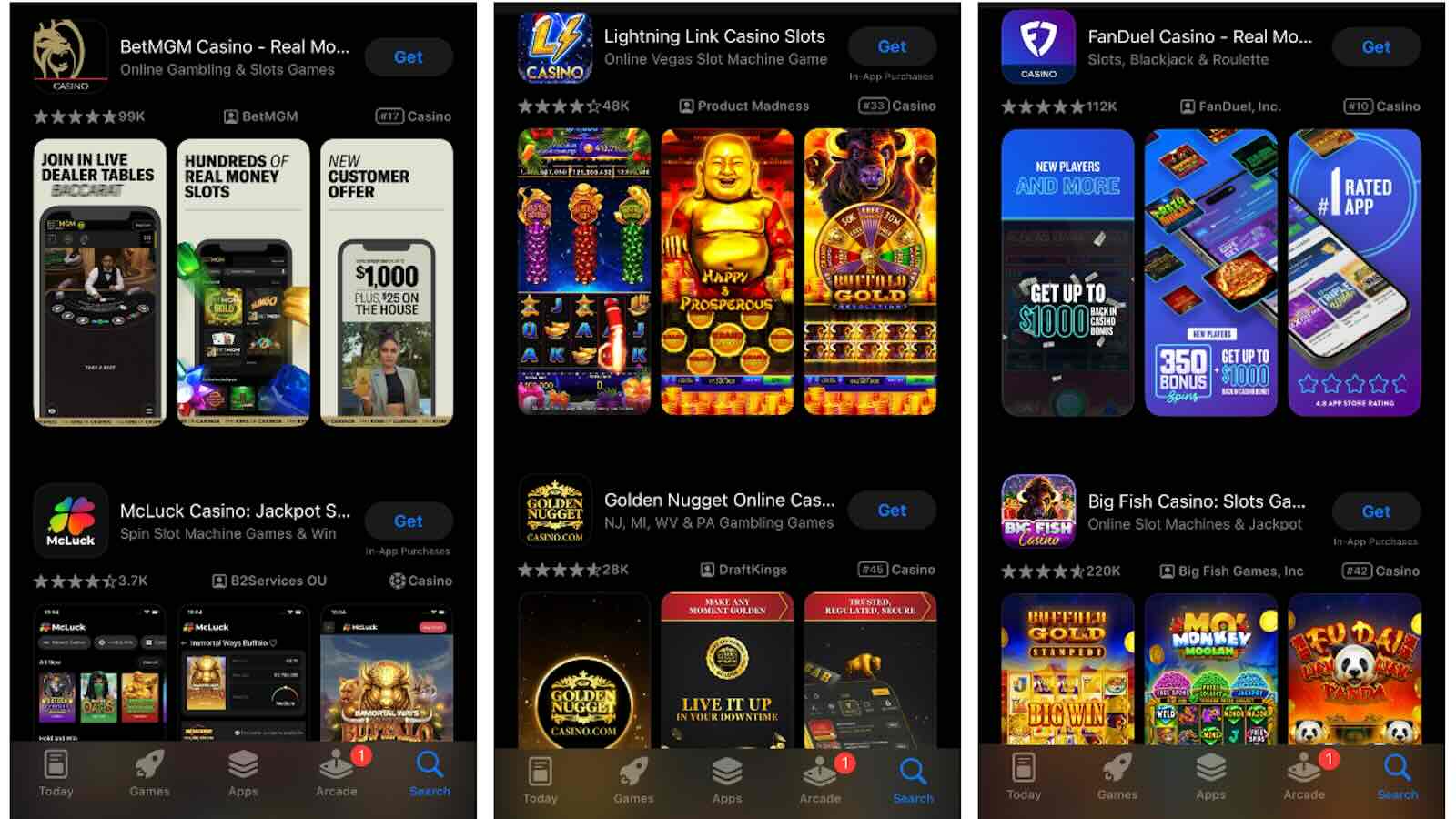

Elsewhere in the realm of Google, in the Play Store — it’s the same story for Apple’s App Store — there’s also the matter of visibility. Appearing in these behemoth stores that come pre-programmed onto every single iPhone and Android phone, well, it comes at a cost. To be exact, 30%.

Assuming an appmaker has the proper technical and legal materials (among them, a legal opinion that the app is compliant with local laws and store policies) to get approved for listing in the store, the tech giants take 30% of revenue on in-app purchases and subscriptions on downloads occurring within those stores.

It’s a hefty cut, but the reach that those tech giants provide is unmatched.

Most traditional social casino operators are operating native apps and do play ball, while most sweepstakes casinos operate via mobile web, meaning users access the game through web browsers, not an app that is downloaded and then works natively within the phone.

“One of the reasons why is due to the cost associated with the prizes — that cost dramatically reduces margins relative to top line revenue, such that it becomes increasingly important for the operators of social casinos that are leveraging a sweepstakes model to avoid the steep app store fees,” Kaufman said.

And these prizes are actually getting a bit more generous than they used to be, in the name of competition. Setting aside some accounting complexities, consider the following analysis from Regulus Partners’ Paul Leyland:

“Back in 2019 VGW was paying out 50% of deposits in prizes, while the ratio now seems to be closer to 75-80%. We can only guess (safely, we think) that new entrants are being at least equally generous. In other words, and unsurprisingly in an increasingly competitive and content-driven environment, sweepstakes casinos have moved from a real payout ratio that looked similar to a lottery to one that looks identical to real-money gambling (note, cash in minus cash out is very different and much cleaner than cash in + cash shaken all about with recycling to create theoretical stakes — theoretical winnings, but it nets to the same figure). Equally pertinently, the accounting treatment of sweepstakes casinos overstates comparable gaming revenue by a factor of about four.”

With the prize costs thus rising, most sweepstakes casino operators have looked to save elsewhere.

“Because they need to get out of these steep app store fees, they’ve opted to make most of their products — and there are exceptions to this — but the majority of the products have chosen to go with mobile web,” said Kaufman.

Mind you, the mobile web route is not necessarily at the expense of quality. Not anymore at least. The rising quality of mobile web games, versus native apps, has made them “almost indistinguishable” according to Stone, a sentiment echoed by Kaufman.

“It used to be the case that native apps performed substantially better than mobile web ones, but nowadays with modern devices and extremely fast internet speeds, the difference in general quality has decreased quite a bit — although native apps still tend to be somewhat quicker and more responsive.”

Stone did point out other advantages to the native app experience: The appmakers can trigger push notifications to flash a promotion or get someone’s attention, or can automatically update the app as it just sits there on the user’s phone.

“But in terms of marketing and how you reach the customer, promotions are still largely email driven,” Stone said. “People have email on their phone. So when they click through a link, whether it goes to the native app or whether it goes to a mobile web, it doesn’t really matter.”

Why choose to go only the social casino route and not both the social casino and sweepstakes casino route? The aforementioned regulatory uncertainty is one hurdle. But at least one of the prominent players is poised to make that leap, and maybe more will soon.

“We recognize that there’s an opportunity for us to leverage and exploit our games and our content and our large network of players and use the sweepstakes promotional mechanic to reinvigorate then drive higher levels of engagement activation and monetization,” said PlayStudios’ Andrew Pascal in November. “Recently, we’ve constituted a formal team internally that’s advancing all the underlying technology tools that we’ll be using to take advantage of that promotional opportunity going forward.”

While so far PlayStudios is the only one of the Top-8 social casino makers to publicly reveal some of its plans, industry sources have advised that nearly all of them are at least exploring the possibility and their capabilities.

Representatives at Playtika and Pixel United did not respond to requests for comment about the potential development of platforms incorporating sweepstakes promotions.

The roads and lawsuits ahead

The calendar has turned to 2025, legislative sessions will soon open across the U.S., and yet another potential competitive threat to the bottom lines of certain segments of the gambling industry has emerged: sports betting prediction markets, an avenue opened thanks to hard-fought legal battles by Kalshi, and recently further exploited by Crypto.com.

Whether the latter development serves to distract or derail the anti-sweepstakes establishment remains to be seen. For now, the various lawsuits against VGW et. al. roll on.

Yet, “litigation has never been a particularly winning strategy for stopping an industry,” said one attorney in the industry who spoke on background.

Said Gantz on iGaming Daily: “I hope that when the cases are dismissed that the people who like to post the complaints give the same airtime to the dismissal orders.”

Indeed, the public relations war will continue on a separate track.

Light & Wonder’s Glaser was asked to what extent, if any, the top makers of social casino games are concerned about the sweepstakes casinos — recently featured in a fair but somewhat unflattering feature in The Washington Post — bringing scrutiny to all online casinos, pure social casinos included.

“No concern whatsoever,” he said.

Asked further about the possibility of onerous new regulations impacting social casinos:

“No concerns at all,” Glaser said.

“As a general principle, [Light and Wonder] shares the view of the American Gaming Association and the industry at large: Support the growth of the legal, licensed, regulated gaming market; and support robust enforcement against illegal gaming,” Glaser added.

On the legislative front, social casinos and real-money regulated online casinos appear to be aligned. The recent Model iGaming Legislation crafted by the National Council of Legislators from Gaming States (NCLGS), announced in November and workshopped at its winter meeting in mid-December, actually includes a provision that would ban sweepstakes casinos.

The task of advancing any iGaming legislation is a fairly steep uphill battle in most states. So the prospect of such a prohibition making it through to a final version of a governor-stamped bill is probably a distant concern.

“The interesting thing to me is that this model legislation leaves freemium [casinos] untouched,” Gantz told Welman. “It’s still an unlicensed, unregulated game, so its legal status is still completely unchanged. And it’s still a giant category, and if you’re going to think about regulating any form of social casino, you should be regulating all of it. I think that’s kind of a glaring hole, personally, but maybe they’ll sort that out.”

This article is long already and hasn’t touched on problem or responsible gambling, which every actor in the space will tell you is the foremost concern. Some of them may be telling the truth.

One truth for sure is that online casinos can be a dangerous product for some people. And another: There are some dangerous and profoundly unsavory things occurring at the fully legal and regulated online casinos.

Consider DraftKings and BetMGM, both of which have made national headlines for lawsuits involving allegations that VIP hosts at the respective companies induced, aided, and abetted persons who were demonstrating clear signs of spiraling addictions to continue playing until the inevitable happened: stealing, bankruptcy, domestic strife, and misery.

Licensure and regulations are only as strong and beneficial to the public as the laws on the books, the regulators enforcing them, and the licensees granted the privilege of doing business.

Notwithstanding that tension, the various interactions between the social, sweeps, and real-money regulated casinos may actually provide an impetus for more states to advance laws sanctioning the real-money kind backed by publicly traded companies.

What remains absolutely certain, for now, is the demand. Humans are gamblers. Gambling and risk-assessment or probabilistic thinking was at one time an evolutionary imperative and is part of our DNA.

In the year 2025, the question is less of whether Americans get the online casino products that they want, but more of where they get them.

“The user is agnostic, so much so, for example, that even black market real money casinos still attract money,” said Stone.

The push and pull will continue, and the direction this all goes seems less likely to be determined in the courts than in the court of public opinion.