Fee And Loathing In Las Vegas

In pushing every imaginable surcharge and up-charge, is Vegas killing the golden goose?

8 min

Anybody remember when Las Vegas was a bargain destination? If you do, you’re among a dwindling minority. “Pain points” in pricing by Sin City are becoming a hot topic with consumers, Casino Reports found.

One person getting an earful about it is former Vegas casino president and retired California regulator Richard Schuetz. He found that “the main bitch I hear from people that have returned from Las Vegas is how damn expensive everything was.”

That may explain why Las Vegas Strip gambling revenue has been trending downward for the past six months, even when visitation was up year-over-year. Schuetz theorizes that “the guests who come to Las Vegas may have the same budget they had last trip, but less is spent on gambling and more on higher priced meals, parking, special fees, or one of the many other line items that increasingly populate the receipts in Vegas.”

The newest of those “nuisance fees,” as they’re called, is “tiered seating” in restaurants, a surcharge for a more desirable table for your meal. Want a window-side view? It’ll cost you extra, bub.

At present, this is only known to be happening in isolated circumstances. But Deutsche Bank analyst Carlo Santarelli recently gave away the plot, writing that MGM Resorts International was “exploring additional ways to generate revenues through creative strategies, including tiered seating in restaurants.”

Money for nothing

MGM was the company that pioneered charging for parking that used to be free. The stated rationale was that attendees to big-ticket Strip events were warehousing their cars in MGM garages while they checked out shows or games. But the fees come with short-term exemptions aimed at Las Vegans, and it is overnight or weekend customers who end up paying the freight.

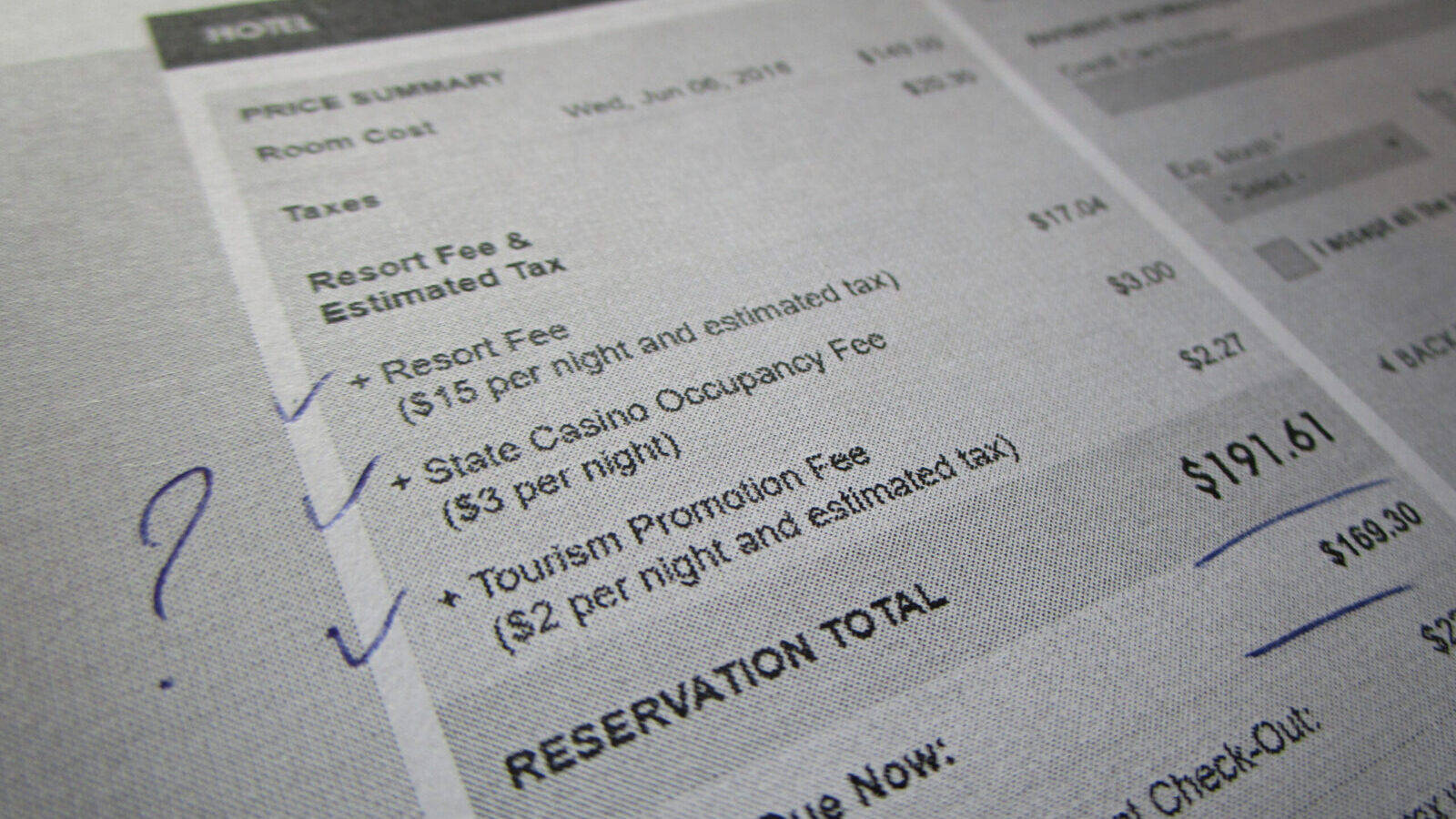

Just in time for Christmas, MGM hiked the parking and resort fees for all its Strip hotels, with parking going up to $20 on weekdays and $24 on weekends. Resort fees top out at $55 per night at premier MGM properties Aria, Bellagio, the Cosmopolitan, and Vdara. (We asked MGM to comment for this story but received no reply.) New kid on the block Fontainebleau Las Vegas presently takes the cake at $56.69 a night.

In the early days of the resort fee, the argument was made (by the casino companies) that the impost was intended to pay for use of the in-room phone, the hotel gym, WiFi access, and “free” newspapers. But one couldn’t opt out of the resort fee, even if the phone went untouched, the computer unused, the newspaper unread, and the gym unvisited.

“A year ago, there was no such thing as a $50 resort fee,” says Las Vegas Advisor Publisher Anthony Curtis, whose publication tracks the levies. “Now there’s a dozen casinos that have $50-plus and they’re heading towards $60.”

It’s worse than Curtis thinks. Casino Reports counted 15 Strip resorts with $50-plus resort fees. A $53-per-night room at Phil Ruffin’s ultra-low-end Circus Circus becomes a $105 proposition after fees and taxes, to cite a random example.

Curtis traces the soak-the-consumer mentality all the way back to 1989, when Steve Wynn opened The Mirage (currently being converted into Hard Rock Las Vegas). “Wynn really drove home the idea of making money everywhere, and that’s when the accountants started looking for different ways to squeeze the customers.”

But the veteran publisher and consumer advocate has seen an acceleration since the Covid-19 pandemic of five years ago. “There was this pent-up demand and taking advantage of the fact people really wanted to get back to Vegas. The casinos realized people would pay an extra tariff to do so.”

Covid, the mother of invention

Coming out of Covid lockdown, casino executives found — and were quite vocal about it — they could operate even more profitably than before by eliminating amenities like low-cost buffets and daily room cleanings. Health-related reasons were the ostensible cause, but companies like Boyd Gaming, a Las Vegas mainstay, weren’t coy about the profit motive.

Customers returning to Las Vegas were also confronted by higher table game minimum bets, as well as narrowed odds. “They’re almost being priced out,” Curtis says of Joe Average players, “unless they go Downtown or to neighborhood casinos.”

Scott Roeben, who rails against “junk fees” from his VitalVegas.com website, agrees. “When I walk into a casino and see a $100 craps table,” he relates, “I’m just mad because I don’t have the funds to play at that table.”

He finds the parking charges “outrageous,” adding insult to injury: “It’s nuts to be dinged $40 or $50 to leave a casino where you just spent money. That’s your first interaction [with the casino] and your last,” one liable to leave a bad aftertaste.

But that bitter taste may not be nearly so acrid as some of under-the-radar fees that restaurants have been known to sneak onto receipts. Curtis’ Advisor recently highlighted a $9 Michelob draft at downtown Hammered Harry’s that carried a 36-cent “resort fee.”

Roeben adds that he’d love to see the Federal Trade Commission go after such picayune gouges but is pessimistic.

Even some of the larger players find they’re getting clipped. Jean Scott, known as the “Queen of Comps” for her ability to suss out casino freebies, says she and her fans are getting jammed. She cites a recent Caesars Entertainment charter flight to Reno. Although she was nominally comped, “I’ve noticed they tacked on $78 and called it some fee for booking. They’re cutting us by small cuts all the time, to think we don’t notice.”

Sky-high fees

Blogger Roeben says that tier-pricing in restaurants is already very much a thing, MGM’s mulling of it notwithstanding. Giada’s in The Cromwell, Ruth’s Chris Steakhouse, Prime at Bellagio, and Martha Stewart’s The Bedford at Paris are all cited by him for their “premium” tables.

But the most celebrated is found in the eponymous restaurant halfway up Paris Las Vegas’ half-sized Eiffel Tower. “Table 56 is right in the corner, where you can see up and down the Strip. That was $40 the last time I looked,” Roeben reports.

A more glaring example involved Scott’s upcoming trip to Paris Las Vegas for a tournament. “I got an invitation to see Garth Brooks, but they wouldn’t give me two [tickets]. Back in the day they would have given me that. Now you’re limited to one promotion per stay. It’s just little things, you know?”

“I’m not going to say it’s criminal because airlines went through the same thing,” by adding fees for checked baggage and seat upgrades. “They found out they could get away with it.” So observes Dennis Conrad, a casino consultant who cut his teeth helping players as “Captain Casino” at Harrah’s Las Vegas. “Casinos are finding out the same thing. But at what price?

“Now it’s going to be a Ritz-Carlton with gambling,” Conrad says of the present-day Vegas experience. “And it’s going to be Ritz-Carlton prices. I’m sure visitation is going to slow down. They’re going to stick to more local and regional casinos, and not taking quite as many trips to Las Vegas.”

Pain points pricked

Conrad isn’t the only one thinking that Sin City is cutting off its nose to spite its face. “They might not stop going to Vegas,” Roeben muses, “but their trip might go from five times a year to once a year, and that’s huge.”

It’s showing up in the marketing, according to Scott. She says she is being wooed by casinos she hasn’t patronized in years, as they dig deeper into their customer databases.

Roeben partially defends the casinos for their pricing practices, saying, “Casinos price what they do at what they think the market will bear. They’re very good at knowing if this price is deterring business, but they’ve missed a beat on the overall effect.”

Still, he says, what customers are buying for their $24 cocktail is a ticket to the Vegas experience, citing Caesars Palace’s new lounge Caspian’s, the former Cleopatra’s Barge: “It’s gorgeous. Can you really expect to get a cocktail for $6 or $8 or $10? Something has to pay for the building, rent, and service.”

Devil’s advocates

Roeben finds the current climate of add-ons and special charges no different from the old days when a $20 bill was slipped to a maitre’d or desk clerk to get an upgraded restaurant table, show seat, or hotel room. “It’s actually convenient for customers to be able to reserve that table for an additional fee because they have guaranteed the experience they’re going to have. They’re going to see the Bellagio fountains as opposed to be being stuck at a table near the bathroom,” he argues.

Conrad concurs, up to a point. “Once they realized there was no pushback, it was like ‘Let’s see how far we can go.’ So they just kept pushing,” he says of the operators. “It used to be Vegas was a value. They made so much on the gaming it paid for anything that they wanted to promote with the food specials, room specials, free rooms, player’s club benefits.”

“The gouging used to be in the casino,” says Curtis, taking up the thread. “It was the way the games were engineered to beat the customer.” Given that, casino bosses could afford a variety of loss leaders (such as the legendary buffets), the better to get players to the tables.

Looking back at Vegas’ “golden age,” Scott recalls that while husbands were flocking to table games, the “dumb wives” were playing slot machines — and learning how to erode the casino’s margins.

“We dumb wives weren’t quite as dumb and, for quite a few years, we were under the radar,” she says with relish. Not so anymore … to the point where Scott took to changing her hair color to stay a step ahead of her nemeses: the people she calls “bean counters,” whom she blames for Sin City’s profit-intensive corporate culture.

Formula One flops

As Conrad says, Strip casinos have not (until recently) seen anything resembling a consumer pushback against high prices and proliferating fees. But that may be changing. Both Curtis and Scott point to the soft numbers posted, two years running, by the Las Vegas Grand Prix, a.k.a. Formula One Weekend.

The Liberty Media-sponsored event, hated by locals for its annual disruption of their daily commute, has seen soft numbers since its inception. A pre-Prix projection of F1 economic impact for the initial race of $1 billion was scaled back to $250 million for the second running.

Nor was the economic benefit widespread. High-end properties, like those in which Wynn Resorts and MGM specialize, reported good business. But Caesars Entertainment found that its lucre was largely confined to Caesars while its mid-level and bargain casinos suffered. The second running of the Grand Prix actually saw casino revenues fall rather than, as was predicted, rise from the year before.

“We saw the prices come down for Formula One this year,” Curtis reports, “because the gouge was too great in Year One and they had to lower prices on everything, from rooms to seats in the bleachers.”

For some, Las Vegas is facing an uncertain future, especially as its primary international markets — Canada and Mexico — have been targeted for economic sanctions. Curtis warns that “the Vegas market is not immune to recessions.”

He ought to know: When the crash of 2008 hit, an encampment sprung up across the street from Curtis’ own Huntington Press. “Those people probably used to stay at the Rio,” he laughs.

“Vegas is a very capitalistic society,” Curtis says. “When people stop coming, for whatever reasons, then Vegas will react with dropping table minimums, dropping the cost of rooms.”

“Have fun. Have a budget,” Roeben advises prospective tourists for now. “The prices are not going to be the same as your hometown. Vegas isn’t your hometown. You’re visiting Disneyland for adults. Disneyland is expensive because it’s great. The same for Vegas.”

Replies Conrad, “It’s amazing, but damn it’s expensive!”