7 Burning Questions On The ‘Sports Event Contracts’ Threatening To Upend Legal Sports Betting In The US

There is a major federalism battle brewing and a lot at stake for states with large sports betting markets

14 min

The table is set and there are two hands gripping the cloth underneath it all preparing to rip away the fabric to alter the scene as we know it, perhaps drastically.

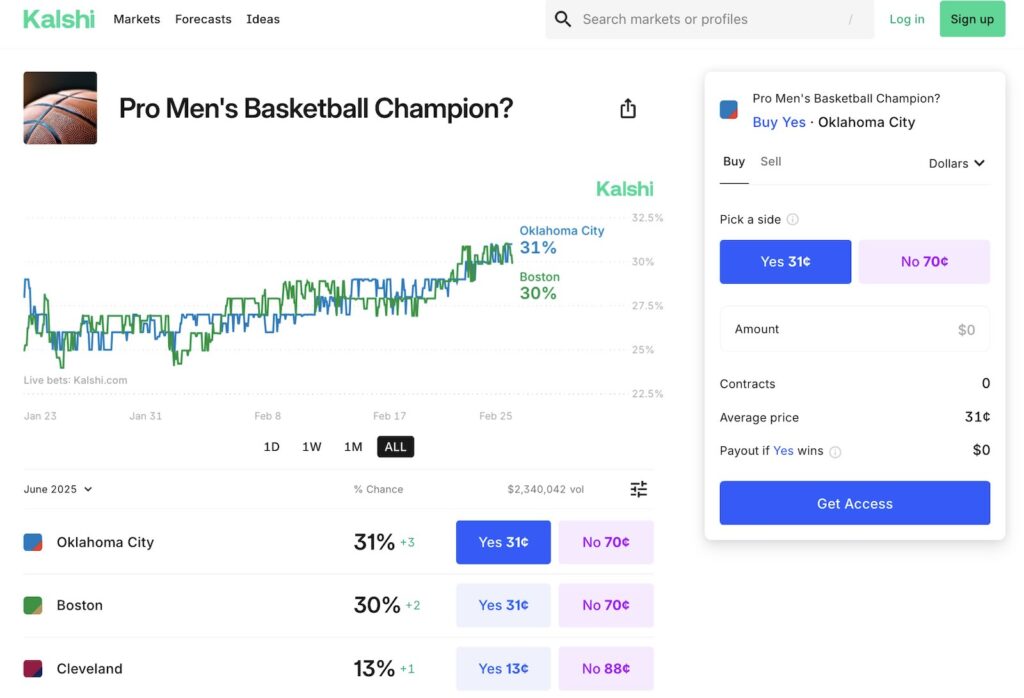

The plates have been slowly shifting around for years now, but in recent months, one Commodity Futures Trading Commission-registered entity in particular, Kalshi, has become emboldened to push the plot forward in a manner that may fundamentally transform the way Americans participate in legal sports betting nationwide.

“Event contracts on sporting events bring this relatively new industry directly into conflict with state-regulated gaming operators,” wrote Nevada Rep. Dina Titus in a Feb. 21 letter to the CFTC regarding a planned series of upcoming roundtables to discuss the issues around sports events contracts and sports betting. “Prediction contracts on sports create a backdoor way to legalize sports betting in states that have not authorized it.”

While Rep. Titus’s concerns are totally valid, the door is indeed open and may remain open if things proceed on the current track where prediction market platforms like Kalshi and Crypto.com maintain and expand their portfolios of sports-related event contracts. This appears increasingly likely to occur based on recent events and political appointments.

As the congresswoman foreshadows, the ultimate clash will pit the federal government against the states or a consortium of states, over their ability to enforce their respective state laws and regulations pertaining to sports betting, and correspondingly, collect the tax revenue and licensing fees produced within their respective borders.

This story has evolved rapidly and there are more questions than answers at the current juncture. This article will identify the key issues now percolating and attempt to parse out and predict where the plotlines go.

1. How exactly might the CFTC-based developments transform U.S. sports betting as we know it?

This brewing federalism battle was foreshadowed by Justice Samuel Alito on May 14, 2018.

“Congress can regulate sports gambling directly, but if it elects not to do so, each State is free to act on its own,” Alito wrote in the majority opinion in Murphy v NCAA, the case that allowed a rapid state-by-state expansion of legal sports betting.

“Justice Alito made clear that Congress could regulate sports wagering,” said Ryan Rodenberg, a Florida State professor who followed the case closely. “As such, the Supreme Court sports betting decision could be a powerful sword for interested parties to push for a federal framework to regulate certain types of sports gaming nationwide via the CFTC.”

While Alito’s words have always been true, what perhaps was not recognized by many, or at least not tested until recently, was that existing federal law in the form of the Commodity Exchange Act of 1936 (CEA) had already laid the foundation for federal regulation of sports betting in connection with its role in the trading of commodity swaps, options, and events contracts. In 1974, the CFTC was created under the CEA as an independent agency to regulate the U.S. derivatives market. In the ensuing 50 years, the agency has updated the rules and regulations to reflect the times.

What Kalshi and Crypto.com did by offering sports-related event contracts (tantamount to bets on the outcome of sports events) is advance the theory that sports-related bets qualify as event contract derivatives, such that prediction markets can lawfully allow trading on them under the CFTC’s purview, positioning the agency as the de-facto regulator of sports event contracts and adjacent products like legal sportsbooks.

This is very much a point of contention, and will be discussed at the upcoming public roundtables focused on prediction markets (and they are discussed here in some of the public comments submitted in advance). But the appointed and incoming CFTC Chairman Brian Quintenz, who previously served as chairman during the first Trump administration and is currently a board member at Kalshi, has called into question the existing prohibition on “gaming” related contracts and the CFTC framework for events contracts in general.

Meanwhile CFTC Acting Chair Caroline Pham has made it clear that while there are “several key obstacles to balanced regulation of prediction markets,” the federal regulator today has a clear focus on making “improvements to the regulation of event contracts to facilitate innovation” and views prediction markets as “an important new frontier in harnessing the power of markets to assess sentiment to determine probabilities that can bring truth to the Information Age.” The point is, both Pham and Quintez appear open to embracing sports events contracts and revising the agency’s regulations to reflect the interpretation.

Here’s the upshot: The federal government can pull rank here and oversee what is, in effect, sports betting in all 50 states. This is the foundational principle of the U.S. Constitution that Alito was referring to in the Murphy opinion. Under the Supremacy Clause (Article VI, Clause 2), federal law will take precedence over any conflicting state laws. This is called “federal preemption” and there are a couple of kinds, express and implied (field or conflict preemption), that theoretically could apply in this situation.

This does not necessarily mean that federally sanctioned sports prediction markets would usurp or sideline state-based regulatory regimes; however, as discussed further below, assuming certain conditions and product breadth at the federal level, a 50-state license to operate may be far more favorable for operators than the existing, fragmented state-by-state approach.

Rep. Titus identifies several key considerations in making the case for preserving the status quo:

“In the United States, gambling is overseen by state regulators with particular expertise and governed by state gaming laws aimed at addressing particular risks and concerns associated with gambling. The Commission is not a gaming regulator. Importantly, each state has their own rules. Some, like Nevada, require those who want to gamble on sports via an app to register in-person. Eight states, like Mississippi, only permit sports betting in-person at a casino. In Florida, a tribal government has the exclusive right to operator mobile sports betting. Importantly, in 11 states (including Texas and California), sports betting has not yet been legalized.

“Each state that legalizes sports betting includes a variety of requirements for consumer protections, responsible gaming, tax revenue, integrity safeguards, and anti-money laundering compliance. Authorizing sports contracts nationally via prediction markets would not include any of these important policy considerations.”

These are valid considerations. Ultimately, how far might the CFTC potentially go in asserting federal authority under the CEA? Very hard to say at this point. So let’s ask another question.

2. These exchange platforms are not full-fledged sportsbooks with a whole suite of options like same-game parlays, player props, and live betting, so why would operators and consumers be attracted to this operational platform?

If the CFTC modifies its regulations and/or interpretations of the applicable laws in a way that embraces sports-related event contracts, there’s a good chance that the exchange platforms could go on to develop more expansive event contract-based products resembling same-game parlays, player props, and all the other popular-for-bettors, lucrative-for-operators betting options. Consider what DFS 2.0 platforms like Underdog Fantasy, PrizePicks, and likewise DraftKings with its Pick6 have produced to conform to somewhat malleable legal definitions.

The point is, once the door is cracked open, the list of prediction markets (or betting options) will likely expand.

“I would expect the CFTC-mediated products to evolve pretty quickly in the direction of modern OSB,” said Chris Grove, partner emeritus, Eilers & Krejcik Gaming. “That’s where the money is. It won’t happen overnight and will likely involve fits and starts, but the American consumer has made it clear what kind of product they like: high-volatility, jackpot-infused bets.”

The eventuality here that would be most attractive to well-funded operators and challenger brands alike is the ability to offer such products:

(a) all across the U.S., including in California, Texas, and Florida, which are all off the table right now (excluding Florida, where Hard Rock has a monopoly); and

(b) potentially without the heavy and ever-increasing tax load, licensing fees ($25 million alone for the right to operate in New York), and revenue-sharing obligations to brick-and-mortar entities, which vary greatly from state to state and are enormous in some states like New York (51%), for example.

This is not to suggest that operators possessing licenses in certain states would abandon them right away, or at all, but if there is no incentive or advantage in a certain state license, then at some point that would seem a logical fiscal move.

So what may unravel is soft-touch federal oversight over segments of the event contracts and sportsbook operator class. This would occur in tandem with state regulations via cooperative federalism, which requires state and federal governments to share power and collaborate on overlapping functions. Federal agencies may set broad standards while allowing states flexibility in implementation.

3. So where might this leave the states — and how might they respond?

For starters, a lot of states, particularly the robust post-PASPA sports betting markets like Illinois, New Jersey, and New York, are probably going to be boiling hot if the feds threaten to upend or materially alter their systems of sports betting regulation, and the substantial tax revenue that it produces.

The states probably won’t be overjoyed in a world of cooperative federalism, where sports-related prediction markets erode some of the dollars feeding into state-based sportsbooks, but leaving the state regulatory structures largely intact in a world of dual regulation probably seems much more palatable.

In a 2020 article in Journal of Legal Aspects of Sport, “‘Standing’ Up for State Rights in Sports Betting,” Professor Rodenberg examines the federalism issues and focuses on the matter of a state’s standing — or a valid legal right to sue — against the federal government in a situation such as the one currently at issue. Rodenberg determined that the states ought to have standing “if the federal government enacts a one-size-fits-all sports betting regulatory approach that is imposed on the states and departs from generally accepted norms of cooperative federalism.” He goes on to cite the work of Tara Leigh Grove: “[W]hen the federal government attempts to ‘nullify’ state law and impose a national rule, the State should have standing to protect the continued enforceability of its law — and thereby preserve the preferences and tastes of its own citizens.”

Such preferences include the kind described by Rep. Titus above, in some states restrictions on betting on props on collegiate athletics, or wagering on in-state teams. The point is that currently the rules and regulations vary state-by-state.

Rodenberg further explains how each state that may object to a federal framework may have a slightly different legal argument unique to its own circumstances:

With standing, states could potentially further a number of claims, including, but not necessarily limited to, those arising under the Intellectual Property Clause, Tenth Amendment, Takings Clause, First Amendment, and Due Process Clause. Indeed, the claims of a well-established sports gambling state like Nevada could differ from the claims of a state that had only recently adopted a legal sports betting framework. Likewise, if any federal bill imposed legalized sports betting on all states, with no opportunity to opt out, a state like Utah — with its anti-gambling stance written into its state constitution — would likely bring suit against the U.S. on additional grounds.

While we don’t yet know for sure what actions the CFTC may take or what authority it may assert, or how any of the legal challenges may play out, the battle lines are clear.

“If [prediction market platforms] can offer sports, then the states have just lost their right to regulate and tax sports betting,” wrote Paul Leyland for Regulus Partners in a Jan. 13 note. “This outcome does not suit any major vested stakeholder; nor does it provide a working legal-regulatory environment, in our view. We believe the Federal government will have to step in to define betting more precisely, potentially by amending the Wire Act (which leaves wagering undefined).”

Elsewhere, a lot of the ardent proponents for preservation of the status quo are correct in such assessments that the offerings of sports-event contracts from Kalshi et. al are, as Bruce Merati of BC Technologies writes, “a direct challenge to the authority of states to regulate gaming within their borders. Bypassing the regulations that states have created to ensure accountability, transparency, and protection for both operators and consumers is a major issue.”

“If platforms like Kalshi and Crypto.com are allowed to operate outside this framework, it could undermine the integrity of the entire system,” Merati expands. “It would create an uneven playing field, where some operators are subject to strict oversight while others operate with impunity. More importantly, it would expose the industry to significant risks, including money laundering, fraud, and the manipulation of sporting events.”

These are valid concerns that will likely garner significant discussion at the planned roundtable discussions.

Ultimately, though, if the federal objectives are to support the kind of innovation that Pham and Quintenz have described, some kind of pre-emption probably will apply and litigation will follow, probably all the way up to the Supreme Court, and the stakes will be high.

Because if the sports contracts available at a federal level do begin to resemble what’s legally accessible in the states, in a matter of time the state sports betting activity may just dwindle until eventually the state coffers are substantially cut out.

4) Is the CFTC equipped to oversee all of this sports activity? What else might occur on the federal level?

There’s a possibility that this upcoming federalism clash provides momentum for the CFTC to adopt certain federal standards for sports betting that both CFTC-registered entities and state-licensed sportsbooks would have to adhere to.

Those may include certain minimum standards, the kind once proffered in the Sports Wagering Market Integrity Act of 2018 (SWMIA) by now-retired Utah Sen. Orrin Hatch and New York Sen. Chuck Schumer.

That piece of legislation aimed to do the following:

- Require that sports wagering operators use data provided or licensed by sports organizations to determine the outcome of sports wagers through 2024, and set requirements for data used thereafter;

- Establish a national self-exclusion list;

- Put in place a variety of consumer protections, including disclosure, advertising, and reserve requirements;

- Establish recordkeeping and suspicious transaction reporting requirements;

- Update existing casino anti-money laundering laws to include sports wagering operators;

- Provide a process whereby states may compact with each other to permit interstate sports wagering;

- Create a National Sports Wagering Clearinghouse that would be responsible for analyzing sports wagering data to identify patterns or trends of illegal activity. Additionally, this Clearinghouse would receive and share anonymized sports wagering data and suspicious transaction reports among sports wagering operators, state regulators, sports organizations, and federal and state law enforcement.

There are some things in there that some stakeholders would love, and others they may like less.

Sports betting to this point has mostly remained a bipartisan topic, which also makes the possibility somewhat realistic that a divided Congress could coalesce around a piece of legislation like SWMIA establishing certain minimum standards for prediction market exchanges offering sports contracts and traditional sportsbooks alike. Or perhaps the CFTC drives the action and Congress does not even get involved.

Another possibility is that coinciding with these certain minimum standards, a sort of self-regulating sports betting body is established, something embracing “cooperative regulation” akin to FINRA (Financial Industry Regulatory Authority), which is a self-regulatory organization for securities broker-dealers that is responsible under federal law and the Securities and Exchange Commission for supervising the group’s member firms.

Another example is HISA (Horseracing Integrity and Safety Authority), established in 2020 to regulate thoroughbred horse racing in the U.S. under the Federal Trade Commission.

This may be necessary because the CFTC as currently constituted may not be equipped to manage the burden itself.

“If we want to allow [sports-related prediction markets], that’s fine. But I wouldn’t make the CFTC the regulator of it, said Tim Massad, former Commodity Futures Trading Commission chairman, per Event Horizon. “The CFTC is a small agency. It’s got other things to do that I think are more central to its mission.”

So perhaps one of these “self-regulatory organizations” — or SROs — becomes part of the answer.

5. How are some of the other major stakeholders viewing this potential upheaval?

One coalition that may enthusiastically embrace the establishment of federal standards for sports betting or an SRO to oversee all of the prediction markets and state-based sportsbooks is the professional sports leagues in the U.S., plus the NCAA.

The reasons are numerous. Chief among them, a federal framework would give leagues more regulatory clarity and the ability to impact policy on the federal level, without having to have conversations or negotiations in 15 or 50 separate states. Take it from NBA Commissioner Adam Silver.

“I was in favor of a federal framework for sports betting [in 2014]. I still am,” Silver said in October. “I still think that the hodgepodge of state by state, it makes it more difficult for the league to administer it. … We take [sports betting] very seriously. As I said sort of day one, it’s not a huge business for us in terms of a revenue stream into the league, but it makes a big difference in engagement. It’s something that people clearly enjoy doing. I’d put it in the category of other things in society that I wouldn’t criminalize them, but on the other hand that you have to heavily regulate them because if there’s not guardrails, people will run afoul and create issues, problems for themselves, potentially for their families or for operations like us.”

The American Gaming Association, which represents the casino industry — regional and international operators alike — has taken a strong position against prediction markets incorporating sports events trading.

“The American Gaming Association opposes current efforts by certain trading platforms and digital exchanges to launch national sports betting circumventing state regulatory frameworks,” said Chris Cylke, the AGA’s senior vice president of government relations. “Legal, regulated gaming in the U.S. — including sports wagering — has worked with state and tribal regulators to develop regulated markets that protect consumers, promote responsibility, and support states and tribal communities in the form of tax revenues.

“We urge the CFTC to reject these proposals, and these companies should cease offering event contracts during the CFTC’s review period. Failure to sustain and uphold state regulatory frameworks poses potential consumer risks and jeopardizes state revenues dedicated towards critical priorities, such as responsible gaming programs and problem gambling services.”

And DraftKings, one of the leading U.S. sportsbook operators, is carefully monitoring the situation. “It’s early,” said CEO Jason Robins on a Feb. 15 earnings call. “We are watching it very actively. It’s certainly something that we have keen interest in seeing how it plays out. So I think there’s some, in the next couple of months, 60 days or so, there’s going to be a CFTC ruling and all sorts of other things, so I think we’ll know a lot more over the next few months.”

6. In a universe with sports events contracts readily available nationwide and sportsbooks in numerous states, where does this leave the consumer?

Great question. The consumer perhaps will end up with more options, though if the federal pathway does eventually erode state-based sportsbooks, perhaps eventually fewer. Or perhaps it causes states to reconsider onerous tax rates to incentivize continued participation in a world where a 50-state reach is possible.

But it’s probably too early to speculate here because we just don’t know yet what kinds of rules, regulations, or SROs may come down the pike.

7. And who would carry the load for problem and responsible gambling initiatives?

Likewise, too early to tell. States currently devote varying amounts of funds and other resources to these programs.

But one other piece of federal legislation already on the table is the GRIT Act (Gambling Addiction, Recovery, Investment, and Treatment Act). From Sen. Richard Blumenthal (D-CT), the legislation would allocate half of the federal excise tax on sports wagers to the states via grants supporting gambling addiction research and treatment.

This bill, endorsed by the National Council on Problem Gambling, has not yet garnered much traction, but it is possible this idea may factor in at some point.

And will all of this action on the sports betting front impact the iGaming legalization impasse in any way?

“I don’t see any immediate interaction between the federal foray into sports betting and the prospects for iGaming regulation,” Grove said. “With that said, we’re in uncharted waters, so one never knows where the boat might go.”

There are a lot of moving parts here, obviously, and a lot more that may get moved around. Take a mental snapshot and then buckle up.